A team of UW researchers have made a discovery that inflammation in one area of the mouth can cause a shift in the body’s immune responses in other healthy parts of the mouth, subsequently resulting in a shift in the microbiome. This discovery may potentially indicate an individual’s susceptibility to developing inflammation in healthy, non-affected sites.

While working on a related study, which characterized and led to the discovery of a new phenotypic response to microbial induced inflammation in the mouth, the team led by Drs. Kristopher Kerns and Jeffrey McLean of the UW Department of Periodontics noticed subclinical changes in the healthy areas of subjects’ mouths, distant from the site showing clinical redness and bleeding typically associated with the early stages of gingivitis.

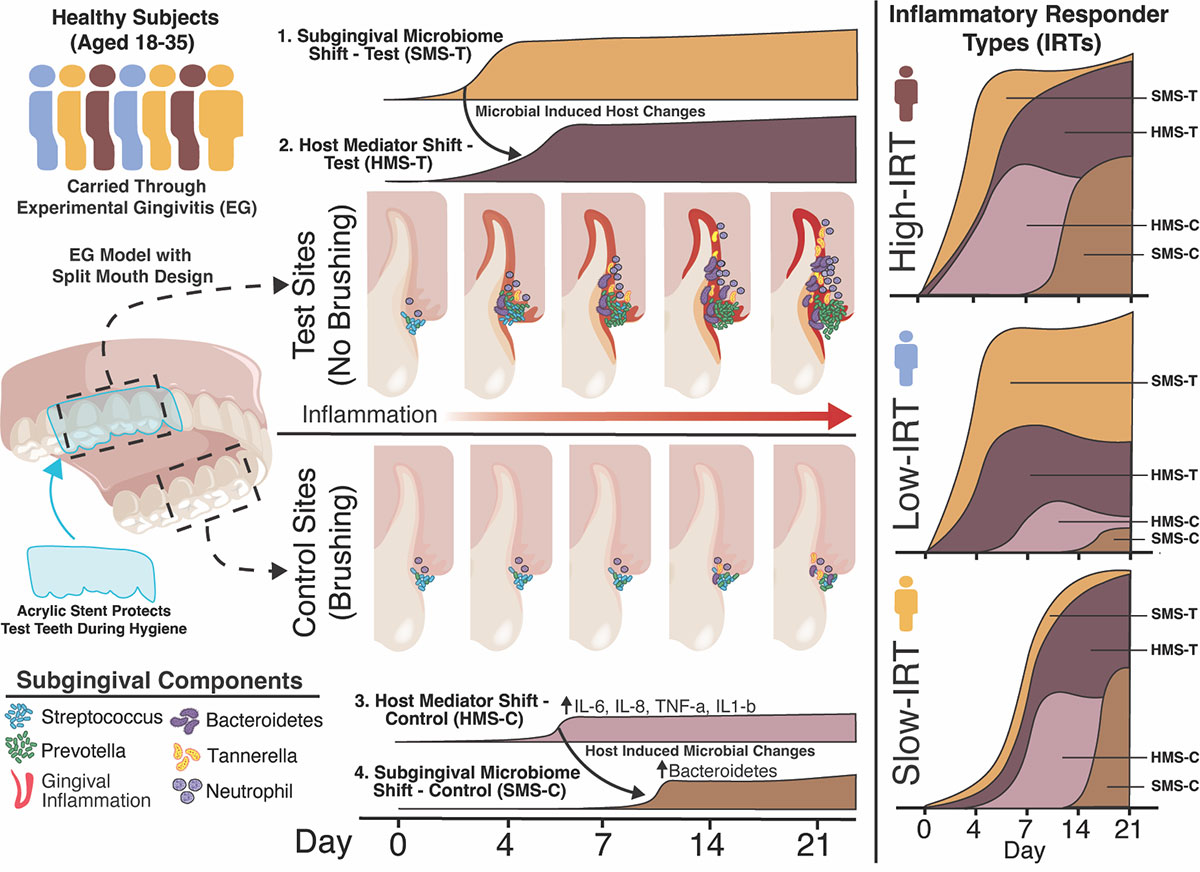

Their recent study, which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), used a split-mouth design where they induced inflammation by having subjects place a stent over a set of three teeth when performing routine oral hygiene. Those teeth were left untreated while subjects brushed the teeth in the rest of their mouth as normal. They had subjects repeat this process for 21 days.

“What our study showed is that you can detect certain host mediator changes in those distant sites, and it’s likely resulting from what’s happening in unbrushed sites located on the other side of the mouth,” said Dr. Kerns. “But what was really exciting is that after that, you can see that the actual microbial community shifts in those healthy brushed sites. Some of the bacteria we detected in those brushed sites are the same bacteria that we detected in an individual’s non-brushed sites which may have attributed to their inflammation.”

Their previous work had already determined that humans have one of three different inflammatory responses to microbial plaque accumulation: high response, low response, and slow response. When they began to notice these shifts in signals in healthy, control parts of the mouth, where normal brushing was maintained for the entirety of the study, they found that those signals were detected in congruence to the subject’s response phenotype.

“Since the high responders get rapid plaque, which results in the rapid onset of inflammation, we can see the signals in those individuals’ healthy sites within the same time frame of about four days on the other side of their mouth,” said Dr. McLean. “So not only can we see changes, but these changes are reflective of what response phenotype each person was.”

While there were no signs of inflammation on the brushed parts of subjects’ mouths, the team has reason to believe that the shift in bacterial composition could lead to increased susceptibility to inflammation in those healthy sites.

“Normally throughout your life you get random spots of inflammation, so this could partially explain how if you get a few random sites, you may have other inflammation spots pop up if it’s not taken care of properly,” said Dr. Kerns.

Periodontal diseases are the most prevalent oral inflammatory diseases in humans. Gum inflammation can lead to gingivitis and eventually periodontitis if left untreated. Identifying which responder type each person is, and determining whether or not inflammation in one part of the gums can increase susceptibility to inflammation in other areas, are two key pieces of knowledge that could help battle these prevalent diseases. That’s why the National Institutes of Health have awarded Dr. McLean and his team a $2.7 million clinical trial to pursue this periodontal research.

Another study, led by Dr. Frank Roberts of the UW Department of Periodontics a handful of years ago found a similar relationship, but in reverse. In that study individuals received a typical periodontal treatment, scaling and root planning, where the hardened bacterial plaque is removed in order to improve the health of tooth sites. This study not only observed the sites that received this treatment to improve but observed that distant non-treated tooth sites also seem to benefit from the treatment.

“Periodontal diseases occur on a spectrum and what we’re really trying to understand is what happens at the beginning during the initiation processes and how susceptibility is aligned with that in order to maybe understand who is most at risk of progressing to more chronic states of periodontal disease,” said Dr. McLean.

This fundamental basic science study was funded through Colgate Palmolive and in part through NIH awards. Dr. Kerns is the lead author of the study and completed this work while receiving funding from the Institute of Translational Health Sciences (ITHS) KL2 Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Career Development Program. Along with the principal investigators Drs. McLean and Richard Darveau, co-investigators from the UW School of Dentistry include Drs. Erik Hendrickson, Diane Daubert, Brian Leroux and Frank Roberts, and others within the Department of Periodontics.

More information about the ITHS KL2 program.