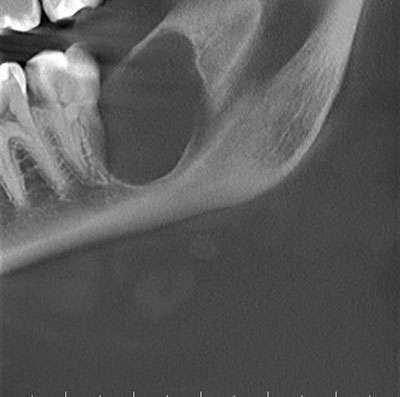

July 2019: Large unilocular radiolucency left posterior mandible

Can you make the correct diagnosis?

This is a 25-year-old female who was referred by her general dentist for the evaluation of a large asymptomatic lytic lesion in the left posterior mandible.

Sorry, you are incorrect!

The corticated unilocular radiolucency in the posterior mandible and the age of the patient are all consistent with the clinical and radiographic presentation of odontogenic keratocyst (OKC). The mild expansion argues against OKC, but not strongly since jaw expansion is described in larger OKCs which this case is large enough to qualify for. The histology is not supportive of an OKC.

Odontogenic keratocyst is an aggressive cyst known for its rapid growth and its tendency to invade the adjacent tissues, including bone. It has a high recurrence rate and is associated with bifid rib basal cell nevus syndrome. The majority of patients are in the age ranges of 20-29 and 40-59, but cases in patients ranging in age from 5 to 90 years have been reported. The distribution between sexes varies from equal distribution to a male-to-female ratio of 1.6:1, except in children. Odontogenic keratocyst predominantly affects Caucasian populations and, if one may judge from the limited evidence provided by the literature, is chiefly of Northern European descent. Odontogenic keratocysts may occur in any part of the upper and lower jaw, with the majority (almost 70%) occurring in the posterior mandible body and ramus. Radiographically, OKCs present predominantly as unilocular radiolucency with well-defined, sclerotic or scalloped borders. They may also present as multilocular radiolucencies. Odontogenic keratocysts of the maxilla are smaller in size when compared to those occurring in the mandible; larger OKCs tend to expand the jaws, but mildly. OKCs can also present as small and oval radiolucencies between teeth simulating a lateral periodontal cyst, in an area of an extracted tooth simulating a residual cyst, at the apex of a vital tooth mistaken for a periapical cyst, or in the anterior maxilla between the central incisors simulating an incisive canal cyst. OKCs grow to sizes larger than any other odontogenic cysts. They usually perforate bone rather than expand it and grow in an anterior to posterior direction. Despite this aggressive growth, they often remain asymptomatic, thus growing to large sizes and hollowing the bone.

Odontogenic keratocysts are significant clinical entities due to their tendency for recurrence and destructive behavior. They are known to have a high recurrence rate, ranging from 13% to 60%. Complete surgical removal is the treatment of choice. Surgery includes enucleation, curettage, enucleation and peripheral ostectomy, and resection depending on the radiographic presentation, location and clinical behavior. Surgery combined with Carnoy’s solution or liquid nitrogen treatment has been effective in reducing recurrence rate. At times, adjacent or associated teeth are extracted in the interest of complete removal. Some investigators advocate marsupialization and occasionally resection of the more aggressive cysts that tend to perforate buccal and lingual bone. Resection is a rare modality of treatment. Most cysts recur within the first three years while others may recur as late as after 16 years. Conservative surgical removal and long-term follow-up is the treatment of choice by most clinicians.

Sorry, you are incorrect!

The radiolucency, the site and to some degree, the gender and jaw expansion are all in support of the behavior of a benign odontogenic neoplasm specifically odontogenic myxoma. The radiographic finding of a unilocular radiolucency is described in odontogenic myxoma but not commonly. Odontogenic myxomas tend to be multilocular. The histology is not supportive of an odontogenic myxoma.

Odontogenic myxoma occurs in the jaw bones, usually in the tooth-bearing areas of the jaws. It is uncommon, benign, but locally aggressive neoplasm. Nearly all cases so far have been described in the jaw-bones. It has the potential for bony destruction, perforation and extension into the surrounding soft tissue structures. A pathologist who is not familiar with the histology of a tooth germ can mistake a myxoid dental follicle for an odontogenic myxoma. Almost 75% of odontogenic myxomas occur in patients around 23-30 years of age with a slight female predilection (1:1.5 male-to-female). It rarely occurs in patients over 50 or under 10 years of age. It occurs almost equally in the maxilla and mandible with a slight predilection for the posterior mandible. A few cases are described in the ramus and condyle, non-tooth bearing areas.

Odontogenic myxoma is a slow-growing, persistent and destructive lesion. Most cases are expansile and can displace and resorb teeth. In the maxilla, they usually invade the maxillary sinuses and at times (though rarely) cross the midline to the opposing sinus. Radiographically, the majority present as Figure 1 This is a partial image of a panoramic view from a CBCT image taken at first presentation demonstrating large unilocular and corticated radiolucency of the left posterior mandible, area distal to tooth #18, expansile and multilocular, though some are unilocular with or without scalloped borders, and rare cases present with a diffuse and mottled appearance, which can be mistaken for a malignant neoplasm. Grossly, this lesion is gelatinous in nature, making curettage alone difficult; the more fibrotic odontogenic myxomas (also known as odontogenic myxofibroma or fibromyxoma) have more body and are easier to curette. Histologically, it is made up of loose and delicate fibrous connective tissue. The fibroblasts are stellate and are suspended on a delicate network of collagen fibrils. Immunohistochemistry studies suggest that the spindle-shaped cells have a combined fibroblastic and smooth muscle typing, suggesting that it is of myofibroblastic origin. Sometimes, this lesion is fibrotic, making it easier to curette.

The treatment of choice is surgical excision ranging from segmental resection with clear bony margins of up 1.5cm to prevent recurrence of the neoplasm. Curettage is with and without cauterization is used for treatment, but is associated with a high recurrence rate.

Sorry, you are incorrect!

The unilocular radiolucency in the posterior mandible with jaw expansion should make one think of unicystic ameloblastoma (UA). The age of this patient is slightly older than the usual range of 10-20 years of age but can be considered. The absence of an impacted tooth argues against UA since 90% of these lesions are associated with impacted third molars. The histology is not consistent with unicystic ameloblastoma.

Unicystic ameloblastomas constitute 13% of all ameloblastomas. They are radiographically unilocular and in 90% of the time are associated with the crown of an impacted tooth. The other 10% are unilocular radiolucency usually associated with teeth such as between teeth. The UA patients are much younger in age and are around 10-20 years of age. They can reach large sizes if not treated in time. They can cause jaw expansion, loosen, displace, and resorb teeth. Curettage is the treatment of choice for UA.

Congratulations, you are correct!

The well-defined radiolucency, the gender, age and jaw expansion are all in support of the clinical and radiographic presentation of central giant cell granuloma (CGCG). The site, however being posterior to tooth #18 is not typical of CGCG, neither is the unilocular radiolucency since CGCG, in general, tend to be multilocular and tend to occur anterior to the first molar. The histology is that of CGCG but primary hyperparathyroidism has to be ruled out despite the young age. The patient is in the process of being tested for that condition.

CGCG is described as a non-neoplastic process of unknown and yet can expand and destroy bone and displace teeth. Over 60% of CGCG cases occur in patients younger than 30 years of age, with twice as many occurrences in females as in males. CGCG is classified into aggressive and non-aggressive types; the aggressive type tends to occur in younger patients and causes disfiguration, especially after surgery. Over 70% of cases occur in the mandible anterior to the first molar tooth.

The usual treatment for CGCG is surgery, ranging from curettage and en bloc to resection. Alternative treatment to surgery are available and include steroid injections; weekly or every 2-3 weeks into the site of the lesion with reasonable success. Calcitonin injections or nasal spray are available and alfa-2a interferon injections, administered 2-3 times per week sub-cutaneous with good results.