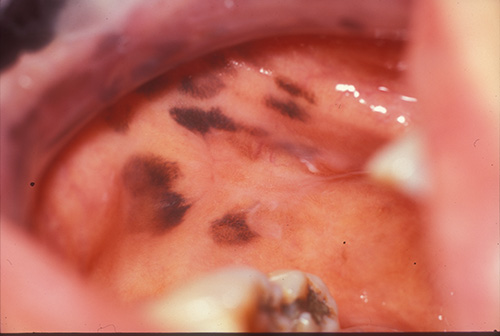

Multiple dark-brown oral macules

Can you make the correct diagnosis?

An 87-year-old non-smoking Asian woman presented with a three-year history of hyperpigmented macules on the buccal mucosa (Figure 1), tongue, maxillary edentulous alveolar ridge, hard and soft palate and lips. The macules are irregular, 4-8 mm in size and are dark brown to black in color. They are otherwise not palpable or indurated. The patient reports that they were first noticed three years ago and that they have increased in number over time.

You are partially correct! — This is what we called it but DDX #2 cannot be excluded

Many diseases fall under this category, most of which do not apply to the oral mucosa. Of the three conditions mentioned (pigmented nevi, malignant melanoma and melanotic macules), only melanotic macules of the mouth have been described in multiples. Primary malignant melanoma of the oral mucosa and oral pigmented nevi only extremely rarely present in multiples.

This case was called multiple melanotic macules based on the histology and the clinical presentation. However, a systemic type disease (see DDX #2) has to be ruled out. Melanotic macules of the lips and mouth are common and are usually single (two thirds) or multiple (one third) (1-3). Melanotic macules of the mouth are usually less than 1.5 cm in size, oval or irregular brown and flat lesions; 85% present on the lower lip, usually near the midline, followed in frequency of occurrence by the palate and gingiva (1-3). The macules on the lips are known as labial melanotic macules while those in the mouth are known as oral melanotic macules. When multiple melanotic macules are identified, it is necessary to rule out systemic diseases (see answer to DDX #2), especially Addison’s disease, Peutz-Jeghers and Laugier-Hunziker syndromes. Oral melanotic macules can occur at any age, with a 2:1 prevalence in females. Histologically, excessive production and release of melanin is identified at the basal cell layer and superficial lamina propria which is the case in this patient. It has an excellent prognosis.

Pigmented nevi are described in the mouth but usually as a single lesion (3). Several types are described, including junctional nevus (rare in the mouth, more common on the skin) and intramucosal (intradermal) nevus, which is the most common nevus of the oral cavity, accounting for 55% of oral nevi followed by blue nevi, accounting for 36% of all oral nevi. The histology and clinical presentation are not supportive of multiple nevi (3).

Oral malignant melanomas (OMM) are exceedingly rare (4-5). They appear to occur more in the Japanese population; this patient is ethnically Japanese. Also, black Africans have a tendency for developing malignant melanomas of the oral cavity more so than that of the skin. Malignant melanomas of the oral cavity are usually discovered late. Also, anatomically this area is difficult to treat surgically. OMM has a worse prognosis than melanoma of the skin. Clinically, it is more common in older men with an average age of 50 (4-5). There is a striking predilection for the palate and maxillary mucosa (about 80%). It presents as a deeply pigmented, ulcerated and bleeding nodule. Sometimes, it presents as non-pigmented nodule. 30% of malignant melanomas of the oral cavity occur in previously pigmented lesions. Bone involvement and exfoliation of teeth is also a common finding. The prognosis of OMM is poor (4-5), with a five-year survival rate of less than 15%. The histology and the clinical presentation in this case are not supportive of OMM.

References

- Kaugars GE, Heise AP, Riley WT, Abbey LM, Svirsky JA. Oral melanotic macules. A review of 353 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993 Jul;76(1):59-61.

- Buchner A, Merrell PW, Carpenter WM. Relative frequency of solitary melanocytic lesions of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004 Oct;33(9):550-7.

- Kauzman A, Pavone M, Blanas N, Bradley G. Pigmented lesions of the oral cavity: review, differential diagnosis, and case presentations. J Can Dent Assoc. 2004 Nov;70(10):682-3.

- Eisen D, Voorhees JJ. Oral melanoma and other pigmented lesions of the oral cavity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991 Apr;24(4):527-37.

- Rapidis AD. Primary oral malignant melanoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003 Oct;61(10):1132-9.

- Erickson QL, Faleski EJ et al. Addison’s disease: the potentially life-threatening tan. Cutis. 2000 Jul; 66(1):72-74.

- Eng A, Armin A, Massa M, Gradini R. Peutz-Jeghers-like melanotic macules associated with esophageal adenocarcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1991 Apr;13(2):152-7.

- Kitagawa S Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Dermatol Clin. 1995 Jan;13(1):127-33.

- Yamamoto O, Yoshinaga K, Asahi M, Murata I. A Laugier-Hunziker syndrome associated with esophageal melanocytosis. Dermatology. 1999;199(2):162-4.

- Taybos G. Oral changes associated with tobacco use. Am J Med Sci. 2003 Oct; 326(4):179-82.

- Cicek Y, Ertas U. The normal and pathological pigmentation of oral mucous membrane: a review. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2003; 4: 76-86

- LaPorta VN, Nikitakis NG, Sindler AJ. Minocycline-associated intra-oral soft-tissue pigmentation: clinicopathologic correlations and review. J Clin Periodontol. 2005; 32:119-122.

You are partially correct! – In order to call it oral manifestation of systemic diseases, we need more clinical information which we did not get in this case

Addison’s disease is a chronic adrenal cortical insufficiency first described by Addison in 1855. This is a rare disease and usually the clinical signs and symptoms do not appear until at least 90% of the functioning cells in the adrenal cortex are destroyed (3, 6). The etiology for the idiopathic may be unknown, but several factors can induce the disease including tuberculosis, adrenal atrophy, massive hemorrhages, or a neoplasm. It can be primary or secondary. Clinical presentation includes hyperpigmentation of the skin (bronzing) and mucous membrane early in the disease process due to the increase of the ACTH level; that in turn has a melanocyte stimulating hormone (MSH)-like effect on melanocytes leading to excessive production of melanin (6). These patients also develop weakness, fatigability, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, hypotension and sometimes salt-craving. Dentists may be the first to discover it, but this is extremely unlikely. Addison’s disease presents as well demarcated brownish macules anywhere in the oral cavity. The multiple oral macules in this case can qualify for this condition (6). However, the skin did not show any discoloration; the patient also denied any of the other signs and symptoms of this condition.

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is an inherited, autosomal dominant condition with 35% mutation (7-8). It is also known as Hereditary Intestinal Polyposis Syndrome. The polyps have a slight tendency, about 10%, for malignant transformation (7-8). The dentist is at an advantage for diagnosing this disease by recognizing the classic presentation of peri-oral flat and small brown spots. They are less than 5mm in size and can affect the anterior tongue, lips and the skin (7-8). They may present around the eyes, nose, hands and feet. The melanotic macules in this patient were not peri-oral or around the anterior tongue. Abdominal pain is occasionally present. The brown spots represent excessive production of melanin (7-8). The histology of the polyps depends on whether or not they are benign or malignant. There is no treatment for the pigmented spots. This patient does not have a history of colonic polyps.

This case may be Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. It is an acquired condition with striking macular pigmentation of the oral cavity presenting most commonly on the lips followed by the hard palate, buccal mucosa, soft palate, tongue and gingiva (9). The macules are dark brown with irregular shapes and shades of brown pigmentation, which was the case in this patient. In addition to the mouth these pigmented macules are described in the hands, vulva (rarely) and the nails (9). The latter affect about 50% of the patients. The finger nail pigmentation is usually longitudinal. It usually affects adults. The appearance of the oral pigmented macules is consistent with this condition but neither nail nor genital pigment was confirmed for a final diagnosis.

References

- Kaugars GE, Heise AP, Riley WT, Abbey LM, Svirsky JA. Oral melanotic macules. A review of 353 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993 Jul;76(1):59-61.

- Buchner A, Merrell PW, Carpenter WM. Relative frequency of solitary melanocytic lesions of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004 Oct;33(9):550-7.

- Kauzman A, Pavone M, Blanas N, Bradley G. Pigmented lesions of the oral cavity: review, differential diagnosis, and case presentations. J Can Dent Assoc. 2004 Nov;70(10):682-3.

- Eisen D, Voorhees JJ. Oral melanoma and other pigmented lesions of the oral cavity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991 Apr;24(4):527-37.

- Rapidis AD. Primary oral malignant melanoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003 Oct;61(10):1132-9.

- Erickson QL, Faleski EJ et al. Addison’s disease: the potentially life-threatening tan. Cutis. 2000 Jul; 66(1):72-74.

- Eng A, Armin A, Massa M, Gradini R. Peutz-Jeghers-like melanotic macules associated with esophageal adenocarcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1991 Apr;13(2):152-7.

- Kitagawa S Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Dermatol Clin. 1995 Jan;13(1):127-33.

- Yamamoto O, Yoshinaga K, Asahi M, Murata I. A Laugier-Hunziker syndrome associated with esophageal melanocytosis. Dermatology. 1999;199(2):162-4.

- Taybos G. Oral changes associated with tobacco use. Am J Med Sci. 2003 Oct; 326(4):179-82.

- Cicek Y, Ertas U. The normal and pathological pigmentation of oral mucous membrane: a review. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2003; 4: 76-86

- LaPorta VN, Nikitakis NG, Sindler AJ. Minocycline-associated intra-oral soft-tissue pigmentation: clinicopathologic correlations and review. J Clin Periodontol. 2005; 32:119-122.

Sorry! You are incorrect

Smoker’s melanosis, first described in 1977 by Heden, is a non-malignant condition associated with the use of smoked tobacco. It consists of excessive pigmentation of the oral mucosa caused by numerous chemical components of tobacco smoke which stimulate mucosal melanocytes (10), and presents in 5-21.5% of smokers. Dark-skinned individuals are naturally prone to mucosal pigmentation, and such pigmentation is even virtually universal among certain ethnic groups; however, dark-skinned smokers tend to present with substantially more pigmentation than comparable non-smokers (3, 10). A Thai study found that this condition has a predilection for occurrence in men in the third and older decade of life. It resolves on its own following smoking reduction or cessation. This patient has no history of smoking.

Birth control pill and pregnancy melanosis (melasma, mask of pregnancy) are discolorations of the skin (commonly) and the oral mucosa (less common) which are associated with pregnancy and the use of birth control pills and hormone replacement therapy (3, 11). This is especially true in olive-skinned females. Pregnancy and estrogen intake leads to melanocyte activity, releasing melanin more actively, especially when the skin is exposed to sun. The pigment is mostly on the middle of the face but can involve the skin on the chin and the forehead. The macules can range from mms to 2 cm in size. In the mouth, the discoloration is usually present on the anterior gingiva (linear), especially lower anterior gingiva (similar to smoker’s melanosis). The discoloration disappears months after delivery or the discontinuation of the hormonal use. The discoloration is enhanced when the patient is also a smoker. This patient is not on hormonal replacement therapy.

Numerous drugs induce oral discoloration attributed to either direct stimulation of the melanocyte activity or to the deposition of pigmented drug metabolites (12); this can sometimes can be the result of combined processes. Several drugs are known to cause mucosal and skin pigmentation including minocycline, tetracycline (12), antimalarial agents (particularly chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine), chlorpromazine, birth control pills, AZT, and ketoconazole. These are a few known drugs among many others.