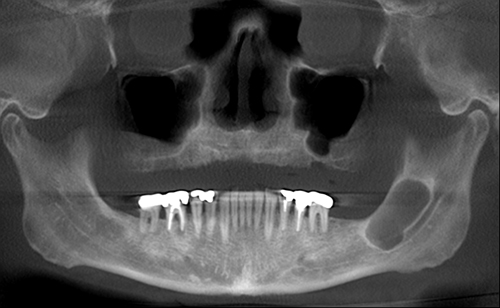

December 2009: Large, unilocular and corticated radiolucency, left angle of mandible

Can you make the correct diagnosis?

This is a 62-year-old male who presented complaining of “pain and swelling” in his left cheek. The patient was prescribed antibiotics for one week.

Sorry! you are incorrect

The differential diagnosis of a unilocular and corticated radiolucency in the area of an extracted tooth should include residual odontogenic cyst, which is usually a periapical cyst but can also be a residual dentigerous cyst depending on the diagnosis of the original specimen. The radiographic presentation of this case which is a unilocular and corticated radiolucency in an area of an extracted tooth would be consistent with a residual cyst. The histology in this case, however, is not supportive of a residual cyst.

Residual periapical cysts are far more common than residual dentigerous cysts, mainly because periapical cysts are the most common odontogenic cysts (1-2). A residual periapical cyst most frequently occurs after endodontic therapy but can also be result of tissue left behind after extraction of a tooth. Residual cysts arise from the remnants of odontogenic epithelium, such as the epithelial rests of Malassez or remnants of dental lamina. Periapical cysts are inflammatory cysts which occur in response to an inflammatory process caused by tooth necrosis, which in turn is caused by extensive caries or tooth fracture (1-2). They are typically in close contact with the affected tooth, usually at the apical portion but sometimes laterally situated.

The preferred treatment for a periapical cyst is endodontic treatment, although teeth are sometimes extracted. Extraction should be followed by curettage of the cystic structure; if the tooth is extracted and the cystic structure, granuloma or abscess is left untreated, the area will not completely heal, leaving behind the soft tissue lesion as a residual periapical cyst or granuloma (1-2). Radiographically, it presents like any other jaw cyst: a unilocular radiolucency with a corticated border. It can be asymptomatic or it can be expansile. Histologically, it is similar to the conventional periapical cysts. The radiographic features in this case can be interpreted as residual cyst.

Sorry! you are incorrect

The radiographic findings of this case could be supportive of traumatic bone cavity, but the location (ramus and condyle) is rare for this lesion, as is the age of the patient; he is too old for this condition. The histology is also not supportive of traumatic bone cavity.

The jawbones are subject to cyst-like or pseudocyst structures such as the salivary gland depression and traumatic bone cavity. Traumatic bone cyst is best called traumatic bone cavity since this condition does not represent a true cyst. Traumatic bone cavity (TBC) is not unique to the jawbones; it is also described in the long bones and is known as a simple solitary bone cyst or unicameral cyst (UBC), occurring mostly in the humerus or femur, close to the epiphyseal plate of children (3). The long bone simple cyst is radiographically similar to the traumatic bone cavity of the jaw and occurs in the same age range. Trauma has been suggested as a possible etiology, along with other non-substantiated theories such as cystic degeneration of a preexisting tumor or of the fatty marrow in the area. The latter theory is without any scientific evidence to support it.

Some reports suggest that it is more common in males (4) while others report equal distribution between males and females (3). The long bone counterpart is more common in males by a ratio of 2.5:1. Most reports agree that the average age of occurrence is below 20 years of age (3-4). These lesions can occur, but are uncommon, over the age of 30. Kaugars reported a higher number of traumatic bone cavity in African-American females compared to the literature (3). The latter patients were over the age of 30 (3-4). This may suggest an association with florid cemento-osseous dysplasia. In the mouth, over 95% of cases occur in the mandible, especially in the posterior premolar-molar area. They rarely extend to the ramus; therefore this case, if it were indeed TBC, would be unique in that it extends very high into the ramus. Also, TBCs are known to cross the midline anteriorly. In one study, 27% were anterior to the canine and some crossed the midline. They are usually unilocular and radiolucent, typically above the alveolar canal and in many cases with a scalloped superior border spreading between the roots of teeth. The latter are vital and are frequently found hanging within the empty cavity. About 25% of the lesions present in the anterior mandible apical to the canine tooth and are usually round and unilocular; they can therefore be mistaken for a periapical lesion, leading to an unnecessary endodontic treatment. Therefore, it is important to test the vitality of the teeth and carefully examine the radiographs for changes consistent with a periapical granuloma or cyst. Large, expansile and multilocular traumatic bone cavities have been described, but are rare. Expansion is not characteristic of TBC but it is described in about 26% of cases (3). They are otherwise asymptomatic. The margins of these lesions range from very well defined to corticated to punched out. Pathologic fractures associated with traumatic bone cavity have been described in the jaws, but are rare. They are, however, more common with those of the long bones.

Clinically, surgeons report an empty cavity at entrance in about two thirds of cases and straw-colored fluid-filled cavities in about one third of cases. Blood clots are also present occasionally. The bony cavity is scraped to generate bleeding, which is considered the treatment of choice for this condition. Other methods of treatment have been tried, such as packing the curetted cavity with autogenous blood, autogenous bone and hydroxyapatite (4). Various other reports demonstrate healing of traumatic bone cavity after injection of autogenous blood, aspiration and after endodontic treatment. These lesions may spontaneously heal, but rarely. Biopsy material consists of fragments of viable bone and loose connective tissue. Osteoclast-like giant cells have also been described in a few cases (3-4). Exploration surgery usually leads to healing. Recurrence is rare but has been described, including multiple recurrences.

Congratulations! You are correct

The odontogenic keratocyst is an aggressive odontogenic cyst, known for its rapid growth and its tendency to invade the adjacent tissues, including bone. It has a high recurrence rate and is associated with basal cell nevus syndrome. It affects patients in the age ranges of 20-29 and 40-59, but cases in patients ranging in age from 5 to 80 years have been reported (5). The distribution between sexes varies from equal distribution to a male-to-female ratio of 1.6:1, except in children. Odontogenic keratocysts may occur in any part of the upper and lower jaw, with the majority (almost 70%) occurring in the mandible. They occur most commonly in the angle of the mandible and ramus (6). Radiographically, OKCs present predominantly as unilocular radiolucencies with well-defined or sclerotic borders; they may also present as multilocular radiolucencies, but rarely. OKCs commonly present as a unilocular radiolucency with scalloped borders. Teeth associated with OKC are vital. OKCs grow to sizes larger than any other odontogenic cysts. They usually penetrate the bone rather than expand it and grow in an anterior to posterior direction (5-6). Despite this aggressive growth, they often remain asymptomatic, thus growing to large sizes and hollowing the bone. Treatment of choice is surgery with cauterization, especially with Carnoy’s solution.

References

-

- Gardner DG. Residual cysts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997 Aug;84(2):114-115.

- Dimitroulis G, Curtin J. Massive residual dental cyst: case report.

Aust Dent J. 1998 Aug;43(4):234-237. - Kaugars GE, Cale AE. Traumatic bone cyst. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1987; 63: 318-324.

- Dellinger TM, Holder R et al. Alternative treatments for a traumatic bone cyst: a longitudinal case report. Quintessence Int. 1998; 29: 497-502.

- Shear M. Odontogenic keratocysts: natural history and immunohistochemistry. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin N Am. 2003; 15: 347-362.

- Oda D, Rivera V et al. Odontogenic keratocyst: the northwestern USA experience. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2000 Feb 15; 1(2): 60-74.

- Reichart PA, Philipsen HP, Sonner S. Ameloblastoma: biological profile of 3677 cases. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol 1995;31B:86–99.

- Adekeye EO, McLavery K. Recurrent ameloblastoma of the maxillofacial region. Clinical

features and treatment. J Maxillofac Surg 1986;14:153-157. - Gardner DG. Some current concepts on the pathology of ameloblastomas. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996;82:660-669.

Sorry! you are incorrect

The location in this case—the posterior mandible and ramus—is supportive of ameloblastoma and the radiographic presentation of a unilocular radiolucency is supportive of the unicystic (cystic) variant of ameloblastoma; therefore, ameloblastoma should be included on the differential diagnosis. However, the lack of facial expansion in this case is not supportive of ameloblastoma; neither is the age and the histology.

Ameloblastoma is one of the most common benign neoplasms of odontogenic origin. It accounts for 11% of all odontogenic neoplasms/hamartomas (7-8). It is a slow-growing, persistent, and locally aggressive neoplasm of epithelial origin. It affects patients in a wide age range but is mostly a disease of adults, at an average age of 33, with equal sex distribution. Reports from Africa and India show a predilection for occurrence in males.

Almost 85% of ameloblastomas occur in the posterior mandible, most in the molar-ramus area, some in the anterior mandible. About 15% occur in the maxilla, the vast majority of these in the posterior maxilla. Solid ameloblastoma is characteristically expansile, radiolucent and multilocular in nature. It can, however, be unilocular and associated with impacted teeth resembling a dentigerous cyst; this is known as cystic (unicystic) ameloblastoma. Cystic ameloblastomas are less aggressive than the multilocular solid counterpart. Ameloblastomas, if not treated, can reach very large sizes with facial disfiguring. They loosen, displace and resorb adjacent teeth. With the exception of jaw expansion, they are usually asymptomatic unless infected; infection may cause mild pain. Parasthesia and anesthesia are extremely rare, unless they are very large in size. Also, ameloblastomas tend to expand rather than perforate the cortical bone. If the latter occurs with extension into the adjacent soft tissue, the ameloblastoma would have a higher tendency for recurrence and therefore would have a worse prognosis than those completely encased by bone (7-8).

Three clinical types of ameloblastoma are described: solid (multilocular), cystic (unilocular) and peripheral (gingival soft tissue). The solid type is treated with resection or en bloc. Resected jaws may require secondary reconstruction (9). Cystic ameloblastomas are treated with thorough curettage while peripheral ameloblastomas are treated with conservative surgical removal.