A team of University of Washington surgeons, including two School of Dentistry faculty members, has rebuilt a patient’s upper jaw and hard palate in one day in a rare procedure that utilized three-dimensional computerized design and implant-bone integration technology.

Dr. Thomas Dodson and Dr. Jeffrey Rubenstein of the School of Dentistry and Dr. Neal Futran of the School of Medicine performed the final step of the 15-hour procedure, called an immediate reconstruction and rehabilitation, on May 16 at the UW Medical Center.

“Only a few centers worldwide offer this service,” Dr. Rubenstein said, adding that this was the first time he knew of its being performed at any Pacific Northwest medical center. The new procedure makes significant use of osseointegration, the process by which living bone grows around and bonds to a titanium implant. It also relies on advanced virtual computer modeling that allowed the surgeons to precisely design a new set of teeth and supporting bone and tissue for an ideal fit.

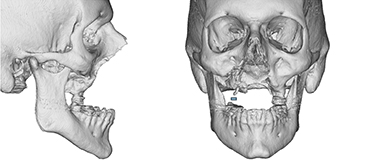

The patient, Marvin Downs, 56, of Tumwater, Wash., had almost all of his maxilla, or upper jaw, and teeth removed in 2003 during oral cancer surgery. Lacking an upper jaw and hard palate, Downs could not speak intelligibly or swallow food or liquid with having it spill from his nose and sinuses.

A specialist at the VA Medical Center in San Francisco, where Downs was then being treated, fashioned an obturator – a kind of denture similar to an orthodontic retainer – that gave Downs upper teeth, covered the 2-centimeter hole in his palate and improved his speech. However, with only one remaining molar to anchor it, the denture could not be firmly stabilized, and grew only more uncomfortable over time. Attempts to adjust it proved fruitless.

In 2010, Downs was referred to Dr. Rubenstein, a maxillofacial prosthodontist, or prosthetic specialist, who determined that there was little hope for improvement with further adjustments or conventional treatment. He consulted with Dr. Futran and Dr. Dodson to see if a better and more permanent solution might be pursued.

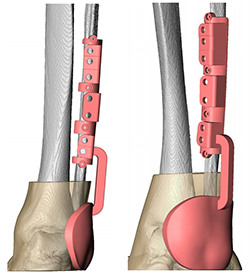

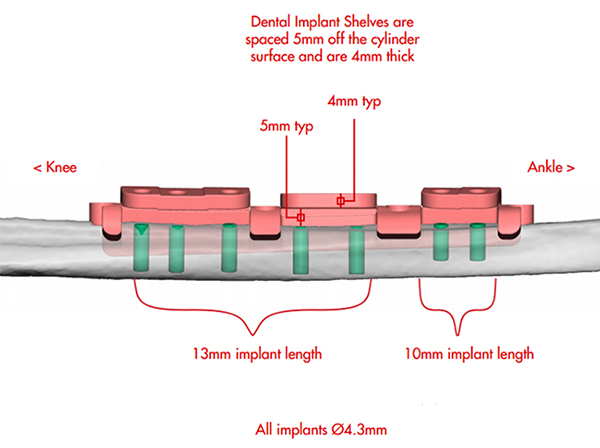

Traditionally, a patient such as Downs would receive grafts from the leg’s fibula bone to reconstruct the missing portions of an upper or lower jaw, Dr. Dodson said. After the grafts and their accompanying tissue and blood supply were allowed to heal for several months, titanium dental implants could be installed in the jaw to anchor new teeth. The teeth could also be installed at that time, but might be delayed further while healing from the implant surgery took place.

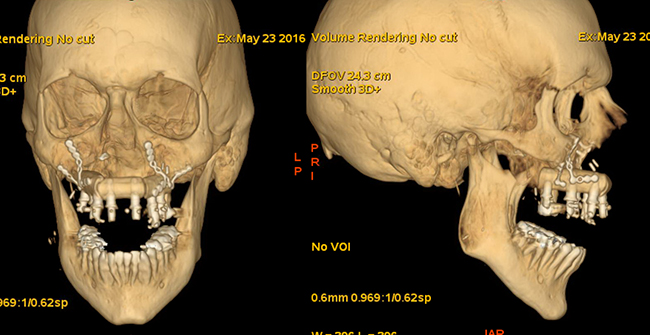

In the new procedure, however, the implants were embedded in the fibula last July by Dr. Futran and Dr. Dodson. On May 16, Dr. Futran harvested the portion of the fibula with its embedded implants, each with surrounding tissue and blood supply. Using a virtually planned, prefabricated cutting guide, the straight fibula was cut into three pieces, which were then arranged to mimic the shape of the upper jaw.

Dr. Rubenstein affixed acrylic teeth to the bone grafts, and the whole complex was transferred into the patient’s mouth by Dr. Dodson and Dr. Futran. Dr. Futran also harvested muscle and skin to seal the hole in the hard palate. In one day, Downs had a restored upper jaw, hard palate, and full set of upper teeth.

“The huge potential advantage is the patient will have [functioning teeth] immediately as opposed to going through a yearlong, multi-stage procedure,” Dr. Futran said. “Granted, he has had a previous step, but this still has far more potential for full rehabilitation in a meaningful way.”

In the conventional method, implants are placed and the dental prosthesis is fitted to the best available bone, but it may not necessarily be the best solution in terms of function or appearance, Dr. Dodson said. “In the new method, an ideal prosthesis is [virtually] designed [and fabricated] and then the implant and graft placement designed to fit the best prosthetic result,” he said.

Over the course of a year, the medical team planned the case jointly, making extensive use of virtual design software. Dr. Rubenstein prepared the prosthesis prototype, which was scanned and fabricated via a computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing process by a firm in North Carolina. The firm also produced a drilling template for positioning the implants.

Dr. Futran performed the May 16 surgery to harvest the bone for the graft and partition it with specially prepared cutting guides based on the virtual planning. He then installed the graft in the patient’s mouth and connected it to the blood vessels in the neck. Dr. Dodson worked with Dr. Futran to stabilize the graft after Dr. Rubenstein connected the new teeth to the implants.

The biggest risk of the surgery would be failure of the blood supply to the new bone structure, which could lead the graft to fail, Dr. Dodson said. Other risks would be failure of the implants to integrate, or to have the prosthesis fit poorly.

However, he said, “I think we can recover from these risks.” With the surgery, Downs should be able to speak clearly and eat and swallow normally, with a much better-fitting, more stable set of teeth. Dr. Dodson also said he did not expect Downs to have any sensory impairment, such as to smell or taste, after the procedure.

“The most challenging aspect is situating the bone and securing it to the remaining maxilla without interfering with the blood supply, sealing the palate defect, and creating an adequate tunnel for the blood vessels from the [bone graft] to reach the neck,” Dr. Futran said. “We are working in a tight space and it all has to fit just right to be successful.”

Dr. Futran and others at UW Medicine oversaw Downs’ initial recovery, and on Thursday the team members said that he was at home recovering slowly but satisfactorily. Downs will require monitoring and adjustment of his new teeth, or repairs if any are damaged, Dr. Rubenstein said.

Each team member brought particular expertise to the case. Dr. Futran is Director of Head and Neck Surgery at the medical center. Dr. Dodson is Chair of the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at the School of Dentistry. Dr. Rubenstein is Director of the School of Dentistry’s Maxillofacial Prosthetic Service, and one of only about 250 maxillofacial rehabilitation specialists in the United States.